Introduction to Redis Streams

- Published on

- Reading time

- 21 min read

- Category

- Under the Hood

Picture this: You have multiple microservices that work mostly independently from each other. Sure, they connect to the same database and maybe share some common libraries but they each have their own domain to handle. But sometimes one service needs to ask another service for some data or notify it about an event. How do you handle this communication in a scalable and maintainable way?

When you need a response with data, a simple HTTP request is usually sufficient. But what if you just need to notify another service about an event? Or worse, what if multiple services need to be notified about the same event? Just sending multiple HTTP requests can quickly become cumbersome and hard to maintain. This is where Redis Streams come into play.

We recently had this problem at my day job at snapAddy and decided to give Redis Streams a try. So let’s take a look together at how they work, how to use them, and what we learned in the past year of using them in production.

Why Redis Streams?

Event-based architecture

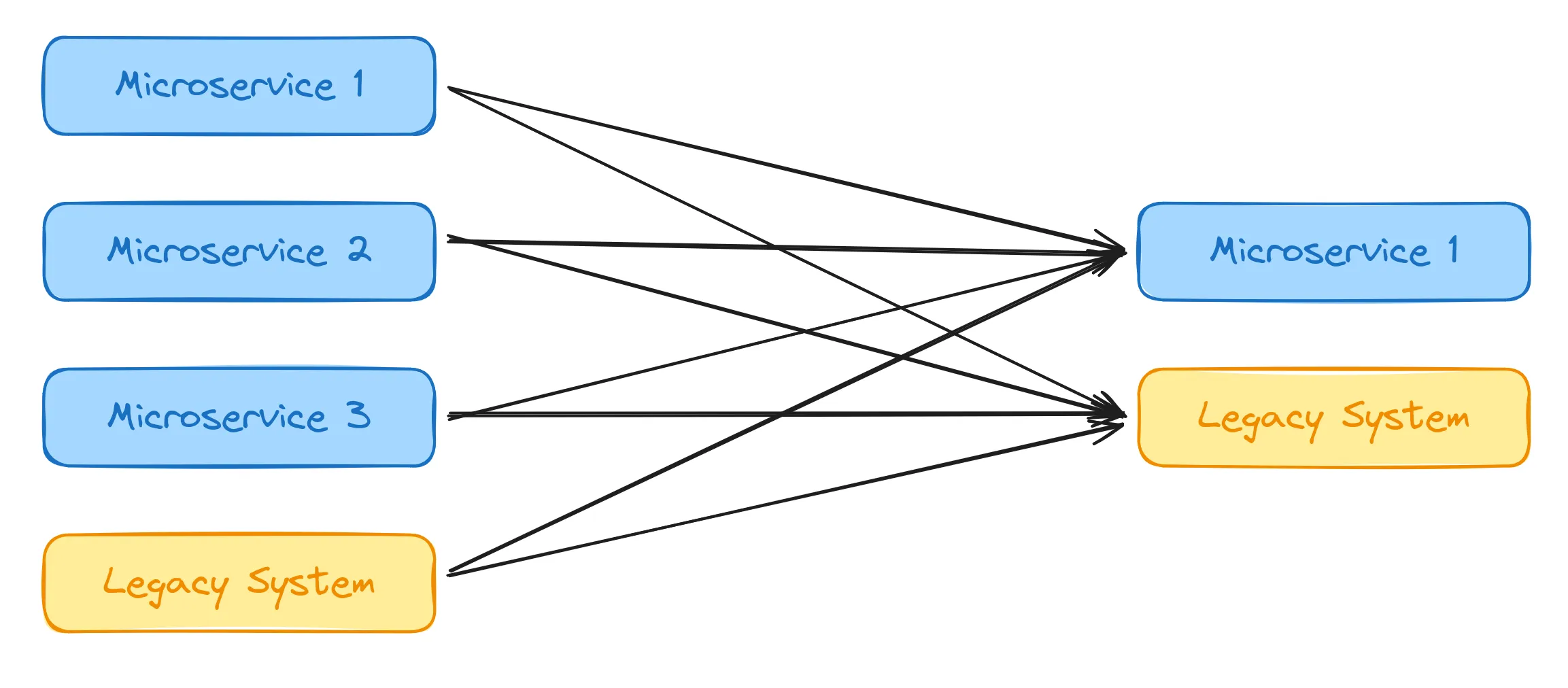

Let’s say we don’t have a shared event bus and we want to trigger some functions in other services. For this to work, we need to manually call each service that needs to be notified about the event. So the communication between those will look something like this:

Every service that can trigger the event needs to call every “consumer” that is interested in said event. With HTTP requests, this means opening a new TCP connection for each call, sending the request and waiting for the response. This can be a lot of overhead, especially with multiple “producers” of the event and many consumers.

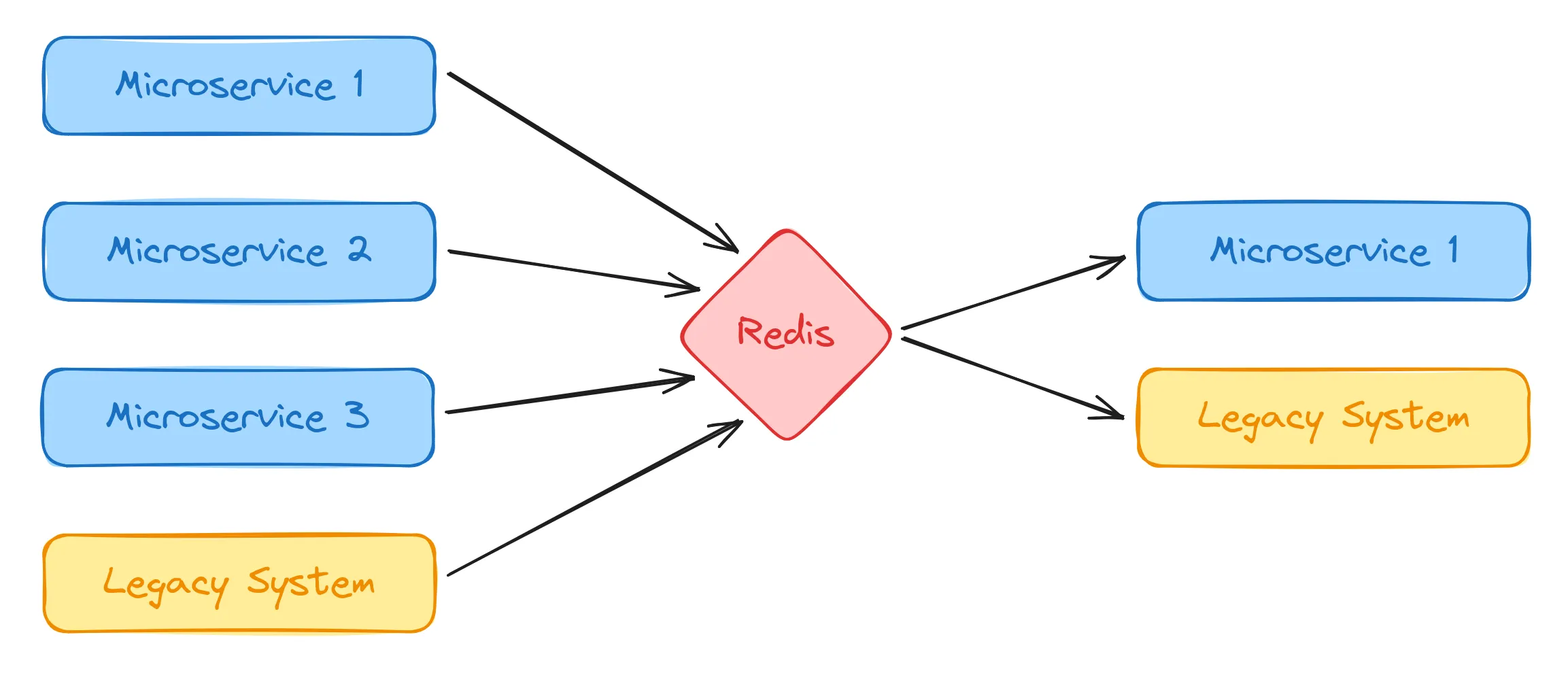

So let’s take a look at what this would look like with a shared event bus:

As you can see this already looks a lot cleaner and more scalable than before. Each “producer” service only need to send the event to the event bus. The service can then continue with other tasks without waiting for any response. The event bus will then distribute the event to all interested “consumer” services and each of these services can then process the event asynchronously in the background.

For us this already has multiple advantages:

- Decoupling: The producers don’t need to know about the consumers. They just send the event to the event bus and don’t care about who is listening. This makes it easy to add or remove consumers without changing the producers.

- Scalability: The event bus can handle a large number of events and distribute them to multiple consumers. This makes it easy to scale the system horizontally by adding more instances of the consumers.

- Fault tolerance: If a consumer is down, the event bus can store the event and deliver it when the consumer is back up. This makes the system more resilient to failures.

- Easy expansion: New services can easily subscribe to events without changing existing services. On the other hand, new services can also publish the same events when they can be triggered from a different place.

As you can imagine, we decided for Redis Streams as our shared event bus. While not perfect for every use case (we’ll discuss some limitations later), we already have Redis in our infrastructure and it fits our use case quite well.

But before we dive into the details of Redis Streams, let’s explain some of the terminology.

Common Terminology

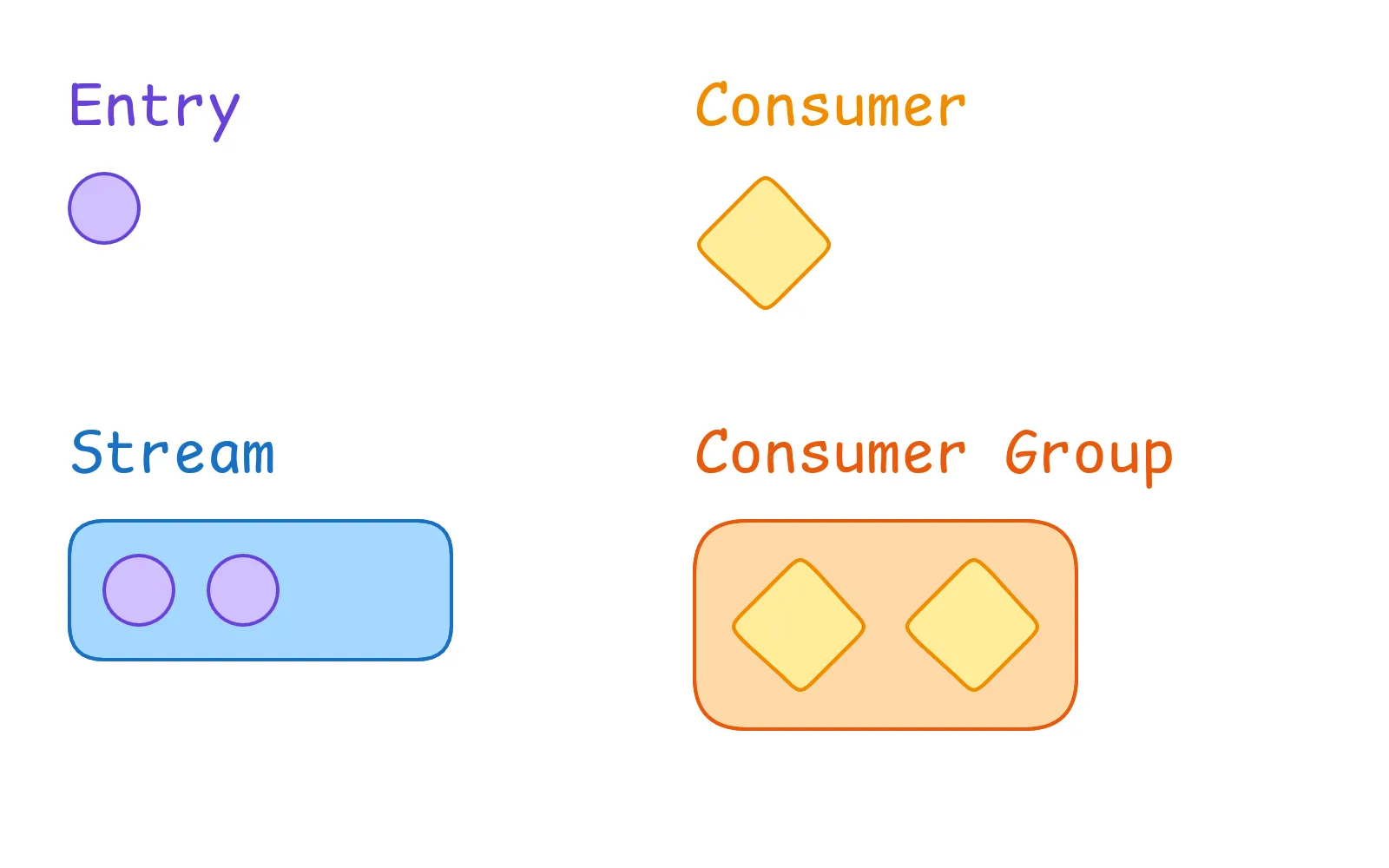

Let’s start with the most basic concept: an entry. An entry is a single unit of data that is stored in a Redis Stream. It consists of a unique ID (based on a timestamp) and a set of fields. Each field has a name and a value, so it is stored as a key-value pair.

A stream is a collection of entries. It also has a unique identifier, which is the key under which the stream is stored inside Redis. A stream contains all entries, basically a log of all events that have occurred. Entries can be added only at the end of the stream. The stream then manages reads, writes and acknowledgements (more on that later).

A consumer can “consume” entries from a stream. Nothing much to say here, just a consumer that can read entries from a stream and then do some action with them. This is usually one (part of an) instance of a microservice.

While a single consumer can not do much on its own, a consumer group can. It is a logical grouping of consumers that bundles them together. Practically this means a group distributes the work among all of its consumers, so that each event is processed but only once. This is usually one microservice that is scaled up to multiple instances. Each stream can also have multiple consumer groups, one for each different microservice. This way one event in the stream can be processed by different services at the same time.

Interactive simulation

To see how the system with a stream, consumer groups and multiple consumers works, I’ve built this small interactive simulation for you to play around with.

Please enable JavaScript to use this demo

Simulation of a Redis Stream with one consumer group

Like in a real application, you can scale the number of consumers in a group up or down (like Kubernetes would to with the service instances). And you can manually add new entries to the stream or enable auto-spawning to see the system work autonomously. What’s a balanced number of consumers for the load coming in? How does the system handle failures?

Once you’ve played around with the simulation we can start to look into how the system works under the hood.

Stream operations

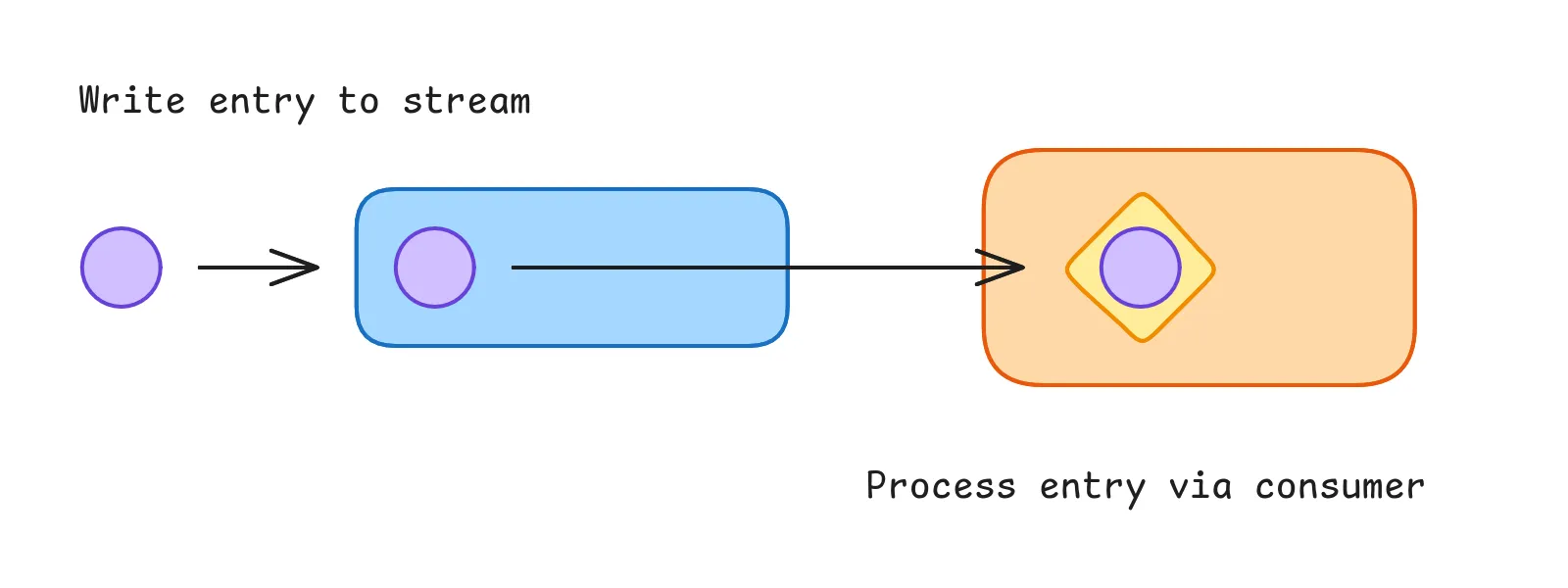

Now that we know the vocabulary, let’s dive into the operations you can perform on streams. This is our end goal for using Redis Streams in our application:

We write a new entry to the stream. Redis will then distribute the entry to all consumer groups for the stream, which in turn means one of the consumers of each group actually gets the entry to process.

Let’s break this down into smaller steps.

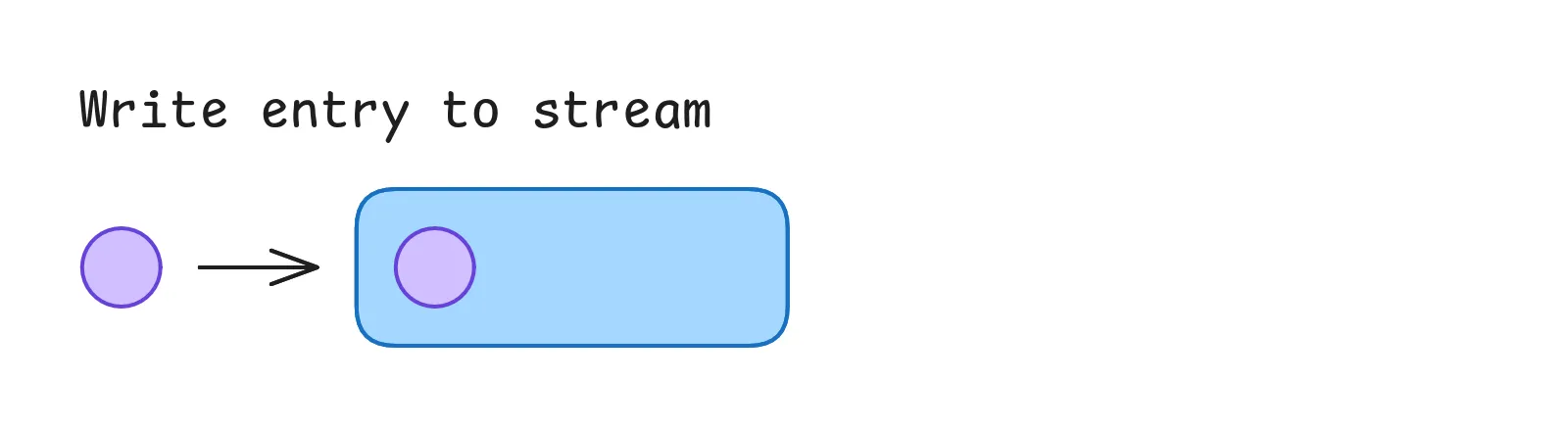

Write an entry to the stream

The first thing we want to do is write an entry to the stream.

For this we use the XADD command.

# Schema

XADD <stream-name> * <field1> <value1> <field2> <value2>

# Example

XADD my-cool-stream * event test

> 1678901234567-0And that’s it! The command automatically creates the stream if it doesn’t exist yet, adds the entry to the stream and returns the ID of the entry. As you can see the ID is a combination of the timestamp when the entry was created and a sequence number (so that multiple entries at the same time still have unique IDs).

There are also some other options for the XADD command, of which I want to highlight the MAXLEN option.

By default, Redis will only add new entries to the end of the stream and keep track of all entries.

But for most use cases this is not practical and just wastes memory.

While you could manually delete entries (e.g. when you’re done processing them) I’d not recommend this for one simple reason:

You don’t know when you’re done with the entry.

Because there can be multiple consumer groups, you don’t know when the last group finished processing the record without manually checking every consumer group.

So we’ll make it up to Redis to cleanup the stream automatically by adding the MAXLEN option to our command.

XADD my-cool-stream MAXLEN ~ 10000 * event test2

> 1678901234567-1With this option you can limit the size of the stream to a certain number of entries.

Redis now automatically deletes old entries when adding new ones to keep the stream size within the limit.

Since we want to process the events as close to real-time as possible this is not a problem as long as we set a reasonable limit.

We also use the ~ modifier, which tells Redis to roughly match the length of 10000 entries instead of an exact match.

Due to the internal representation of the stream, Redis can efficiently delete a small group of entries when the limit is reached, instead of deleting one entry at a time.

So since we don’t care about the exact length this performance improvement is a no-brainer to activate.

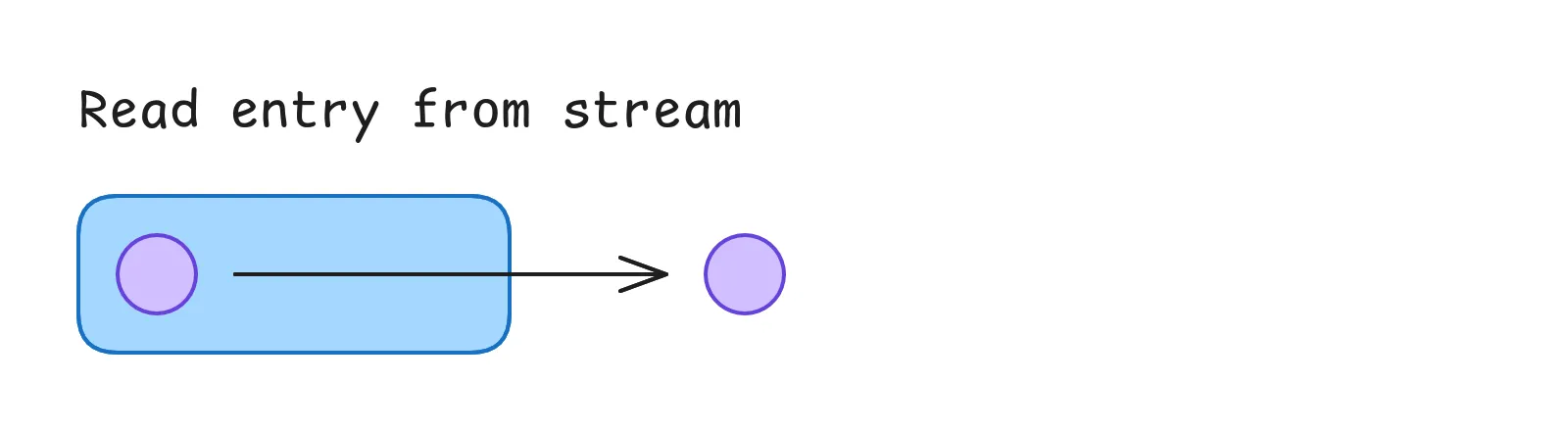

Read entry from stream

Now that we have created two entries in our stream, let’s read them back.

Simple read

To start, we’ll do a simple read:

# Schema

XREAD COUNT <length> STREAMS <stream-name> <id>

# Example

XREAD COUNT 1 STREAMS my-cool-stream 0

> [[my-cool-stream, [1678901234567-0, [event, test]] ]]This will simply read the first entry (with an ID greater than or equal to the specified ID 0) from the stream.

While this looks really easy to do, it has some problems.

XREAD does not keep track of which entries have been read already, so repeating the same command will result in the same entry being read again.

We’ll tackle this in a moment, but first there is another problem:

Our read is pull-based, meaning the client has to actively request the data.

Instead we want Redis to notify us when a new entry is available automatically.

So let’s run this command instead:

# Schema

XREAD BLOCK <ms> STREAMS <stream-name> <id>

# Example

XREAD BLOCK 0 STREAMS my-cool-stream $

> [[my-cool-stream, [1678901234568-0, [event, test]] ]]This introduces two new concepts that already improve our read operation:

With BLOCK we can tell Redis to wait for a specified duration before returning an empty response.

When this is set to 0, Redis will wait indefinitely until a matching entry is available.

So our code doesn’t need to loop and poll new entries all the time, but can just wait for Redis to respond.

This way we basically hacked together a push-based solution (as long as we always query again after processing a previous entry).

We also told Redis to read the stream beginning from $.

This is a special identifier that tells Redis that we’re only interested in entries added after we sent the command.

With other words it doesn’t matter which entries are already in the stream, we just want to read the next one that comes in.

While this is already better than the previous solution, but we still have two problems:

- Other instances could process the same entry at the same time.

- Entries coming in while we’re processing another one could be lost.

Managed read via consumer group

So we need to step up our game and introduce a consumer group.

# Schema

XGROUP CREATE <stream-name> <group-name> <id>

# Example

XGROUP CREATE my-cool-stream my-consumer-group $

> OKThis XGROUP CREATE command creates a new consumer group for the specified stream.

The group will then manage our read position and ensure that each entry is processed exactly once per group / microservice.

Note that we can use the $ identifier that we just learned about to start reading from the first entry that was added after the group was created.

So if we add a new group later, we don’t need to process all existing entries in the stream again.

If you call this command multiple times, Redis will return an error that the group already exists. You can ignore this one, since afterwards you have the same result as if the command was executed successfully.

Finally we can use the XREADGROUP command to read from the stream via the consumer group:

# Schema

XREADGROUP GROUP <group-name> <consumer-name> COUNT <length> BLOCK <ms> STREAMS <stream-name> <id>

# Example

XREADGROUP GROUP my-consumer-group my-consumer COUNT 1 BLOCK 0 STREAMS my-cool-stream >

> [ [my-cool-stream, [1678901234568-0, [event, test]] ] ]This is the longest command we’ve seen so far, but let’s break it down piece by piece:

Similar to our read command we can use the COUNT and BLOCK options to fake our push-based communication.

In addition we use another special identifier >.

This tells Redis to give us the next entry that was not yet processed by any other consumer in the group.

So the group will manage our reads between multiple instances and ensure that each entry is processed only once.

This makes our application horizontally scalable by just adding more instances of the same service / more consumers to the group.

And the rest of the command is pretty self-explanatory. We obviously need to specify the group name to tell Redis which group we want to use for the read. And the consumer name is used to identify the consumer within the group for the PEL (more on that later). I just always set this to a UUID so we can scale multiple instances of our service without duplicate consumer names.

Confirm processed entries

The last thing we need to do is to confirm that we have processed the entry.

This is done by calling the XACK command:

# Schema

XACK <stream-name> <group-name> <id>

# Example

XACK my-cool-stream my-consumer-group 1678901234568-0

> 1This just acknowledges that we have processed the entry for the given consumer group, so no other consumer in the group will process it again.

That’s basically all you need to know…

Except if you cannot process the entry because e.g. your instance was forced to shut down during processing. So unfortunately, we need to handle these errors.

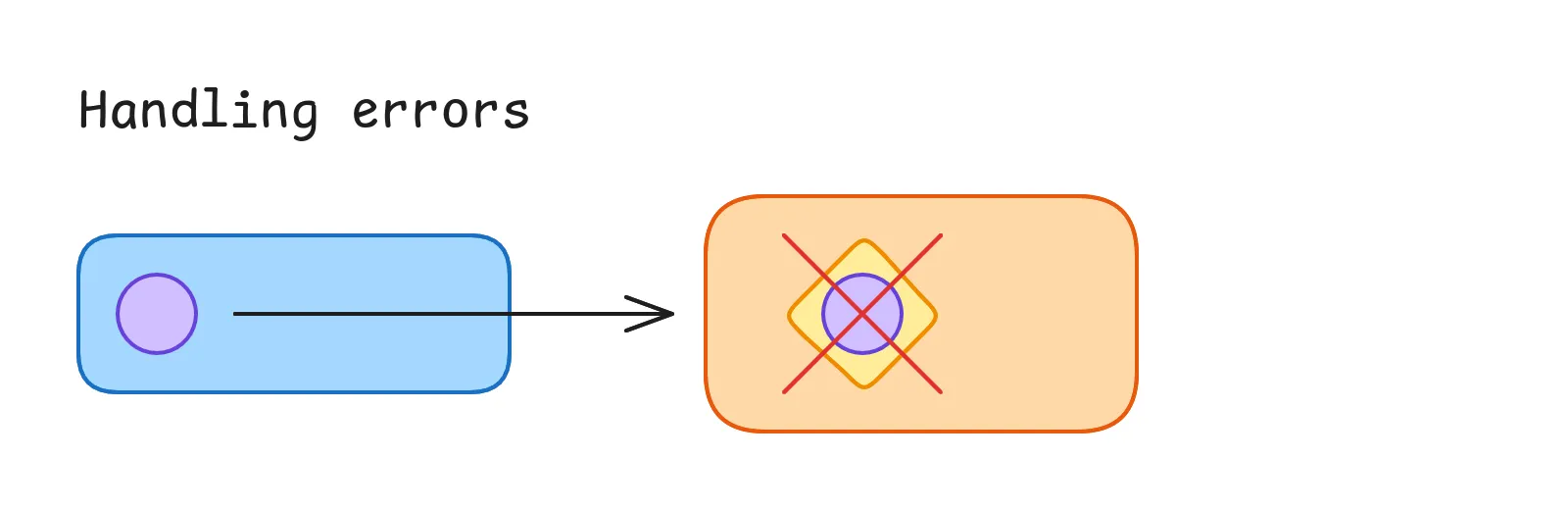

Handling errors

As said our service sometimes might not be able to process the entry. This could be caused by some external service not being available, a bug in our code or the instance being shut down during processing. So for one reason or another, the entry can not be acknowledged against Redis. That’s why we need to check for pending entries.

Checking for pending entries

This is where the previously mentioned Pending Entries List (PEL) comes into play.

When a consumer reads a record via XREADGROUP Redis will automatically assign the entry to this consumer and put it into the consumers PEL.

Once the consumer is done processing the entry and sends an acknowledgement, the entry will be removed from the PEL and the entry will be marked as processed for the entire consumer group.

This means with the correct command we can check for pending entries.

So let’s checkout the XPENDING command:

# Schema

XPENDING <stream-name> <group-name> IDLE <ms> <start-id> <end-id> <count>

# Example

XPENDING my-cool-stream my-consumer-group IDLE 10_000 - + 1

> [ [1678901234567-0, my-consumer, 13_468, 1] ]Firstly we need to specify which stream and consumer group we want to check for pending entries.

Next we want to specify the IDLE time in milliseconds.

This can be used to filter out entries that are probably still being processed by a consumer.

So we’ll set this some some reasonable time, after which we’ll assume the processing has failed when not acknowledged yet.

Then we have two special identifiers again:

-means start reading from the beginning of the stream (minimum ID)+means read until the end of the stream (maximum ID)

So we’ll scan the whole stream for any pending entries.

And lastly we limit the number of entries to 1 again.

This is not a hard requirement, but fits our existing logic of only reading one entry at a time.

In our actual production logic we added an additional reclaimed flag to mark the entry as being re-processed.

With this we could execute different logic depending on if the entry was already tried once or not.

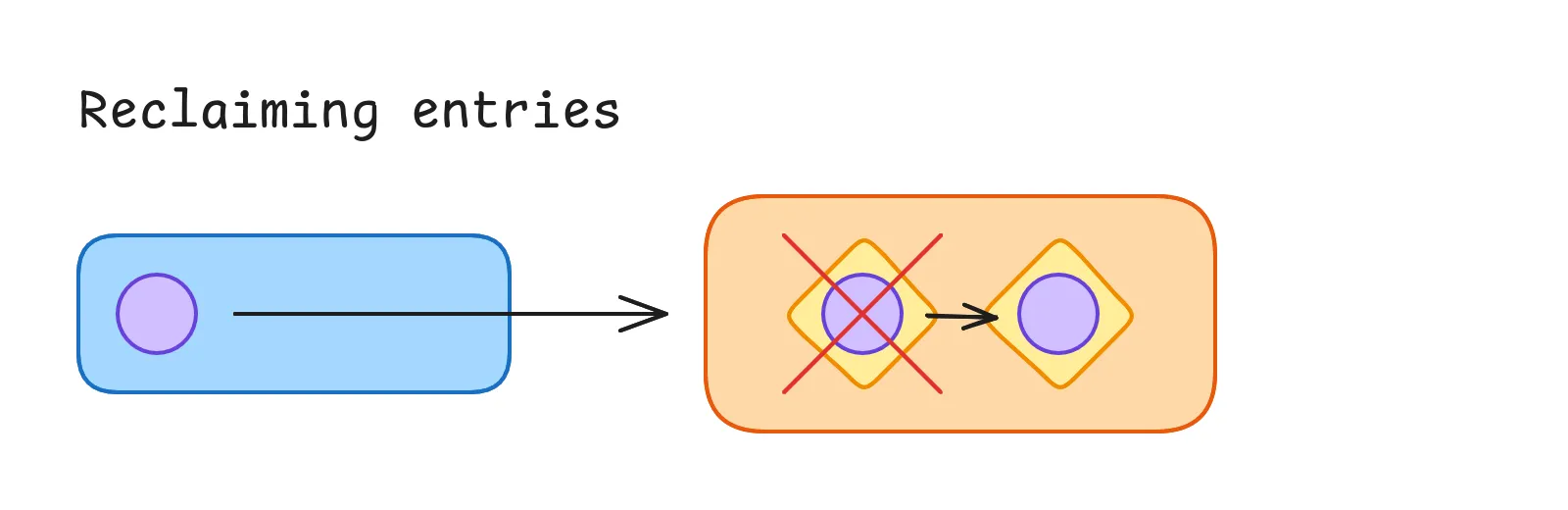

Recovering failed entries

Now that we have a pending entry that was not acknowledged within our specified idle time frame, we can continue and try to recover it.

For this we can use the XCLAIM command:

# Schema

XCLAIM <stream-name> <group-name> <consumer-name> <min-idle-time> <...ids>

# Example

XCLAIM my-cool-stream my-consumer-group my-consumer 10_000 1678901234567-0

> [ [1678901234567-0, [event, test]] ]With this command we can now claim pending entries from other consumers.

Similar to the XREADGROUP command, we need to specify the stream, group and current consumer name, so Redis knows where to read the entries and who is processing them now.

We also specify a minimum idle time again, since we want to make sure that no other consumer tried to reclaim the entry in the meantime.

Meaning Redis will automatically reject our claim if the entry was already claimed by another consumer and thus resets the idle time again.

So we’re also safe against race conditions here and ensures that we can scale our application horizontally by adding more consumers to the group.

After a successful claim, we can process the entry like before.

When we’re done, we can acknowledge the entry for the group by using the XACK command as usual.

And that’s all we need to recover from failures and make sure every entry is processed once to the best of our ability.

When (not) to use Redis Streams

Before I give you some tips and insights of what we learned using Redis Streams in production, let’s discuss when and when not to use them. For this I’d like to compare three different communication patterns:

- Request & response

- Publish & subscribe (pub/sub)

- Streams

The request & response pattern is a simple way to communicate between two services and probably the most well known one. It’s the most basic pattern without any need for additional infrastructure or a mediator. Just one service that sends a request to another service and waits for a response. This is useful when you need some data from another service to continue your own operation. However the requesting service must know all interested parties so it’s not suitable for a distributed, event-based system.

So let’s compare this with the publish & subscribe pattern. This is more suited for an event-based system comparable to Redis Streams. Similar to streams, the publisher can send events to a mediator but does not get an answer from any consumer. For pub/sub, every consumer gets a copy of the event, so there is no concept of a “group”. This also happens in real-time and messages are typically not stored for later consumption. This means that when there are no subscribers, the messages are lost and cannot be recovered. You can compare this pattern to an online multiplayer game. Every online player needs to receive the same information at the same time, while players that are offline don’t need to receive the message. (Redis also provides a pub/sub solution but I’ve not yet worked with it.)

And lastly the streams pattern we took a look at in this post. Similar to pub/sub, streams are suited for event-based systems, where the producer doesn’t need to get an answer. But this time, every event has to be processed once (per group), so it is stored for later consumption until a consumer is ready to process it. Consumer groups are used to group multiple consumers (instances) together, so that events are not processed multiple times. In addition, multiple consumer groups can be used to process the same event independently for different actions. In our case, we can publish events to the Redis Stream when the user does something in our app or dashboard which then needs to be processed asynchronously in the background.

Tips for production ready Redis Streams

We now covered the basics to start using Redis Streams in an application. All of the above commands can be used to build an event-based architecture that is highly scalable, fault tolerant and durable. You also now (hopefully) know if Redis Streams are the right tool for your application or if you should use something else.

All of the above commands were Redis native ones that can be used with the Redis CLI.

But of course, you can use any Redis client library that supports these commands.

Our backend is written in TypeScript and NestJS and we were already using the official ioredis library by Redis.

So we also used this library for our streams implementation.

Unfortunately the return types of these commands are horrible, so we built an internal wrapper library around it which is:

- End-to-end type safe from adding entries to reading and processing them

- Provides a super easy to use API for subscribing to streams which already handles all the retry logic and stuff for us

- Brings a

@RedisStreamdecorator that allows us to integrate them with our NestJS services like any other route handler

We’re using this setup for almost a year now and it works quite well. But there were some small issues in our implementation that we discovered over time. Fortunately we were able to fix all of them. So here are some tips for production ready Redis Streams from our experience:

Handling service shutdown gracefully

Depending on your runtime environment (e.g., Node.js), a SIGTERM might not shut down the Redis consumer correctly and block the application from shutting down.

For us this was caused by the blocking Redis connection that was waiting for new messages to come it and not resolving its promise.

So I’d recommend to not only use a condition that tells your consumer to break the loop of trying to read messages, but also:

- Use a

Promise.racewith a promise that resolves when the shutdown signal is received (similar to anAbortSignal) - Force the Redis connection to close by calling

redisClient.quit()

But be careful with this approach! We did exactly that and had issues with messages being processed multiple times. This was caused by our processing also blocking the shutdown. So we killed the Redis connection, continued processing the current message, but then could not acknowledge it anymore. Thus my suggestion is to check whether the consumer is currently processing a message before closing the Redis connection to prevent this edge case. This is also built into the simulation above, where a consumer will be displayed grayed out but not removed when it still has entries assigned.

Preventing infinite message re-processing

Talking about consumers re-processing messages when they shouldn’t:

We didn’t want to retry messages over and over again until they are evicted from the stream.

So we implemented a configurable maximum number of retries for each message, after which messages will be treated as permanently failed.

Redis automatically keeps track of the number of retries for each message, which is returned by the XPENDING command.

So we can easily filter out messages with too many retries.

But there is no native way to mark messages as failed in Redis Streams.

Initially we just ignored messages with too many retries in our logic. But this lead to our consumers always reading the oldest message (with too many retries), over and over again instead of skipping it. So instead we now do two things with these messages:

- Acknowledge them via

XACKeven though we couldn’t really process them. - Track the number of permanently failed messages via a custom metric in our monitoring system.

This way the “error queue” is not blocked by these messages and other ones can be retried. And we can monitor the number of permanently failed messages to keep the error rate under control and see when to investigate further.

Pro tip:

If you cannot process a message due to an expected error (e.g. a missing prerequisite, missing data), you can mark the entry as processed via XACK directly.

There is no point in retrying these messages since they will probably fail again.

Cleaning up old consumers

Lastly, Redis keeps track of every consumer that ever received messages from a stream.

But when using volatile consumers like Kubernetes pods that scale up and down in combination with UUIDs for consumer names, this can lead to a lot of unnecessary consumers in the consumer group.

While not tragic, we decided to clean up these consumers periodically with a custom script that runs every night.

Doing this is a simple call to XGROUP DELCONSUMER but there is one caveat:

When a consumer still has pending messages and is being deleted, its messages will become unclaimable.

So we can not delete the consumer during it’s own shutdown, but need to do it every night, while checking for any pending messages before deleting it.

Conclusion

After using Redis Streams for almost a year, we have learned a lot about its capabilities and limitations. I’m proud to say that we have made the correct decision to use them as part of our application architecture and we’re starting to expand our usage of them in other parts of our application (at least where it makes sense). That’s why I decided to share our experience with you.

Now you too know about the basic concepts of Redis Streams and some commands to interact with them. You learned how to use them, when to use them, and got some insights into their limitations. For more information, check out the awesome Introduction to Redis Streams documentation right from the source.

Have you used streams or other event-based systems in your application? I’d love to hear about your experiences and stories as well.

Latest Post

Related Post

Building an Astro Integration

After building a custom loader for Astro to load content from PocketBase, I wanted to make the developer experience even better. In this post, I show you how I built an integration with a custom toolbar for viewing and refreshing PocketBase entities, complete with realtime updates.

- Published on

- Category

- Under the Hood